How US Air Travel was Affected by a Grand Canyon Disaster

On June 30, 1956, Trans World Airlines Flight 2, a Lockheed L-1049 Super Constellation with 64 passengers and 6 crew members departed Los Angeles bound for Kansas City at 9:01 AM on an IFR (Instrument Flight Rules) flight plan and a planned altitude of 19,000’. Three minutes later, United Airlines Flight 718, a DC-7 with 53 passengers and 5 crew members departed Los Angeles climbing to 21,000’ bound for Chicago. The planes’ paths would cross with 2,000’ of vertical separation approximately over the Grand Canyon.

On June 30, 1956, Trans World Airlines Flight 2, a Lockheed L-1049 Super Constellation with 64 passengers and 6 crew members departed Los Angeles bound for Kansas City at 9:01 AM on an IFR (Instrument Flight Rules) flight plan and a planned altitude of 19,000’. Three minutes later, United Airlines Flight 718, a DC-7 with 53 passengers and 5 crew members departed Los Angeles climbing to 21,000’ bound for Chicago. The planes’ paths would cross with 2,000’ of vertical separation approximately over the Grand Canyon.

Shortly after takeoff, TWA requested permission from the TWA ground operator to ascend to 21,000’ to avoid cumulus cloud buildups. The ground operator contacted Los Angeles Air Route Traffic Control Center who denied permission stating, “You have United 718 crossing his altitude – in his way at two one thousand [21,000].” The ground operator relayed to TWA 2, “TWA Flight 2, unable to approve two one thousand.” The captain then requested “1,000 on top” (permission to fly 1,000’ above the clouds, still under instrument flight rules). This practice allowed the separation restrictions normally applied to be suspended and required the individual pilot to maintain his own separation visually from other aircraft. The controller then issued a clearance with a warning: “ATC clears TWA Flight 2, maintain at least 1,000 feet on top. Advise TWA 2 his traffic is United 718, direct to Durango, and estimating Needles, California at 9:57 am.” The ground operator relayed the clearance. TWA climbed.

In 1956, ATC radar coverage was non-existent over most of the US. Commercial airliners reported positions to controllers and estimated their time to the next position. At 10:13 am, the Salt Lake controller received the latest position reports from both aircraft. Interestingly, he knew both planes were at 21,000’, and would cross each other’s paths over the Painted Desert at the same moment, but he did not advise the airliners. According to the CAA (Civil Aeronautics Administration) rules, he was not required to as they were flying visually. As the two aircraft approached each other with TWA’s Constellation to the left of United’s DC-7, the pilots were likely maneuvering around towering cumulus clouds.

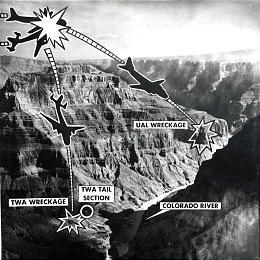

At 10:30 PST, the two aircraft struck each other over Grand Canyon National Park. The DC-7’s left wing struck the Constellation’s tail and then slid on top of the fuselage, its propeller blades slicing through the rear cabin and causing immediate loss of control to United as its tail assembly separated from the rest of the aircraft. Sixty to 90 seconds after the collision, at 10:31, the Salt Lake City controller received a garbled radio transmission from TWA First Officer Robert Harms “Salt Lake, ah, 718 . . . we are going in.” It plunged in a four-mile vertical dive to the base of Temple Butte on the north slope of the canyon at the confluence of the Colorado and Little Colorado Rivers at an estimated speed of more than 475 mph (700 feet per second), penetrating 20 feet into the sheer wall, annihilating the aircraft. A fire ensued. The tail section came to rest 550 yards north of the impact area. Light debris (such as magazines, blankets, and personal effects), fell over a large area along both banks of the Colorado River from the explosive decompression which occurred instantly at initial collision.

At 10:30 PST, the two aircraft struck each other over Grand Canyon National Park. The DC-7’s left wing struck the Constellation’s tail and then slid on top of the fuselage, its propeller blades slicing through the rear cabin and causing immediate loss of control to United as its tail assembly separated from the rest of the aircraft. Sixty to 90 seconds after the collision, at 10:31, the Salt Lake City controller received a garbled radio transmission from TWA First Officer Robert Harms “Salt Lake, ah, 718 . . . we are going in.” It plunged in a four-mile vertical dive to the base of Temple Butte on the north slope of the canyon at the confluence of the Colorado and Little Colorado Rivers at an estimated speed of more than 475 mph (700 feet per second), penetrating 20 feet into the sheer wall, annihilating the aircraft. A fire ensued. The tail section came to rest 550 yards north of the impact area. Light debris (such as magazines, blankets, and personal effects), fell over a large area along both banks of the Colorado River from the explosive decompression which occurred instantly at initial collision.

The impact of the DC-7’s propeller with the Constellation’s fuselage left its outer left wing panel mangled and unable to produce adequate lift and a damaged engine unable to produce power. Capt. Robert F. Shirley was unable to control the aircraft and it descended rapidly in a left spiral, crashing into the top of an 800’ sheer cliff on the south side of Chuar Butte and burned.

All 128 on board the two flights perished.

At 11:51 when Aeronautical Radio Communications in Salt Lake City could not establish radio contact with either plane, Air Route Traffic Control Center issued a missing aircraft alert. The search for the two missing aircraft did not last long. On the day of the crash, a pilot operating a Grand Canyon scenic flight heard the report of the missing aircraft. Having recalled seeing smoke in the canyon earlier in the day, he went out for a second look that evening and confirmed the wreckage was the two missing aircraft.

Recovery efforts were difficult due to the rugged terrain and unpredictable air currents at the site. The operation was one of the most extensive and dangerous rescue and recovery operations in the history of the National Park Service, and was one of the first times helicopters were used as a recovery vehicle in the Grand Canyon. Military personnel, Swiss and American mountain climbers, river guides, and citizen volunteers joined in the recovery effort. The wreckage of both planes was left on the buttes until the Park Service contracted a firm to remove it in the late 1970’s. Small pieces of the TWA aircraft remain yet on the hillside in the canyon. Since the United DC-7 crashed high on a bluff in an inaccessible location on Chuar Butte, pieces left in the rocky crags of the cliff’s south face can still be spotted by passengers on river rafts passing through the river corridor.

Recovery efforts were difficult due to the rugged terrain and unpredictable air currents at the site. The operation was one of the most extensive and dangerous rescue and recovery operations in the history of the National Park Service, and was one of the first times helicopters were used as a recovery vehicle in the Grand Canyon. Military personnel, Swiss and American mountain climbers, river guides, and citizen volunteers joined in the recovery effort. The wreckage of both planes was left on the buttes until the Park Service contracted a firm to remove it in the late 1970’s. Small pieces of the TWA aircraft remain yet on the hillside in the canyon. Since the United DC-7 crashed high on a bluff in an inaccessible location on Chuar Butte, pieces left in the rocky crags of the cliff’s south face can still be spotted by passengers on river rafts passing through the river corridor.

A mass funeral for the victims was held on July 9, 1956 at the canyon’s south rim.

The area was designated a National Historic Landmark, the first landmark for an event that happened in the air. It is now closed to the public.

With 128 dead, the Grand Canyon crash was the first to result in the death of more than 100 people and was the deadliest US commercial airline disaster, the largest air crash of any kind on US soil at the time. As the public learned more about the lack of sophistication of ATC, it demanded action.

The investigation of the accident was particularly difficult due to the terrain at the crash site and lack of real time flight data found on airliners today. The Civil Aeronautics Board issued the following statement as probable cause for the accident:

The Board determines that the probable cause of this mid-air collision was that the pilots did not see each other in time to avoid the collision. It is not possible to determine why the pilots did not see each other, but the evidence suggests that it resulted from any one or a combination of the following factors: Intervening clouds reducing time for visual separation, visual limitations due to cockpit visibility, and preoccupation with normal cockpit duties, preoccupation with matters unrelated to cockpit duties such as attempting to provide the passengers with a more scenic view of the Grand Canyon area, physiological limits to human vision reducing the time opportunity to see and avoid the other aircraft, or insufficiency of en route air traffic advisory information due to inadequacy of facilities and lack of personnel in air traffic control.

Due to public demand, the Federal Aviation Act of 1958 was passed, dissolving the CAA and creating the FAA (Federal Aviation Administration) which was given total authority over American airspace and procedures. ATC facilities were modernized and the use of radar, more stringent flight rules, and more rigorous training of pilots and air traffic controllers have greatly reduced the likelihood of a similar accident ever recurring.

June 30, 2016, will be the 60th anniversary of the crash. The influence of the 1956 crash has been felt around the world, as ATC has been standardized and has drastically improved air safety.

Paula Vail, retired American Airlines pilot and co-founder of Canyon Ministries